One of the many side effects of COVID on the travel industry is that the loss of revenue from tourists is causing trouble in places where the economy relies to some extent on tourism dollars.

The chain reactions set off by the cessation of a stream of income can have devastating effects on the lives of people all along those economic chains.

One of the areas where the loss of tourism revenue has particularly devastating effects is conservation in Africa. We are at a unique time in history where many of the world’s most magnificent species of animals are on the verge of extinction. A significant part of the efforts being made to protect them is funded by tourism companies.

Travel Industry Stakeholders

Those companies, whether tour operators, lodge proprietors or others within the travel industry, are among the few who have the wherewithal and care enough to take care of these vanishing wilderness areas and the wildlife who still manage to survive the human onslaught.

If something causes a disruption in the flow of their financing, the results over time can be disastrous to our biological legacy. If tourism-funded efforts to save these animals and their habitats fall away, the earth could really lose them forever. And with things like this, there are no second chances.

While we’re busy attending to our massive complexes of problems in the world today, they could just slip away while no one is looking, so to speak.

Saving the Vanishing Wilderness

The “charismatic wildlife,” such as the great elephants, lions, giraffes, and gorillas, may go the way of the saber-toothed tiger and the woolly mammoth. They may survive only in picture books for our grandchildren and their children, who may never get to see them. And no matter how much they may wish it, we can’t go back and retrieve them once they’re extinct.

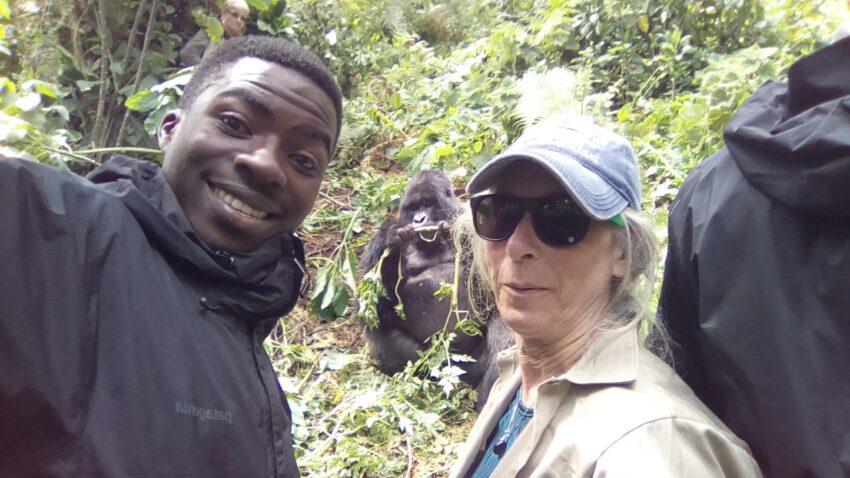

The mountain gorillas of Africa, one of the closest human relatives, and therefore one of the greatest treasures in the animal kingdom, diminished to only 242 in 1981 – dangerously close to the forever zone. Now the number is 1004. It’s still perilously low, but it’s moving impressively in the right direction. Without conservation efforts, much of it financed by tourism income, we might have already lost them.

Sad to say, the gorilla species has no enemy except human beings, who are fueled in their killing and capture by a black market that makes it profitable to steal babies or kill the adults to behead them to sell the heads.

In many cases, the great animals are dying because humans are destroying their habitats. But the good part of the story is that many people in the tourism business of these areas are driven more by the desire to protect these areas and animals than they are by economic gain.

An Inverted Values Hierarchy

Strange as it seems in a world that often seems to run strictly on money, it is a fact that many of the tourism operations I have run into in Africa are fueled by a value system that puts saving the beauty of the wilderness over making a profit.

Those who own the lodges and private game reserves are usually not people who went into business to get rich. It tends to be the other way around. They are often companies founded by people who became rich in some other enterprise, and were moved to purchase tracts of land to preserve. They offer the wilderness experience to visitors, whose fees feed the financial system that fuels the conservation efforts.

This process of preserving the wilderness is a huge team effort that takes place from the corporate board rooms of the big international tour operators, down to the safari guides, housekeeping, and food service people employed by the lodges – who take visitors on safari and channel some of the profits into supporting the conservation efforts.

Trouble on the Ground

I spoke recently with one of the people on the ground in Rwanda, who is part of the gorilla trekking tourism infrastructure, and got a view of what is happening at Volcanoes National Park. Unfortunately, it’s a disturbing picture of what happens when the faucet of funding is turned off.

Moses Nezehose Nice was born and raised in Rwanda. He has worked for years as a driver/guide. He started as an intern, and was recruited by Kagoma Eye Safaris Limited, first in an office job. Later he worked in the field as a guide and hired out as freelancer for various safari operators.

This year he decided to take the plunge and start his own company, Gorillas Expedition Safaris. But since the drop-off in tourism, when the global pandemic set in last March, he’s only escorted one group of travelers.

With his years of hands-on experience and his understanding of the specialized practice of gorilla trekking, starting his own business was a solid bet. For many years the demand for gorilla trekking safaris has been growing. Gorilla trekking is justifiably seen as one of the premier experiences offered by the travel industry anywhere in the world. Because the protection of the gorillas requires strict adherence to the limitations required that keep them safe and healthy, access is tightly limited.

Only a small number of permits are offered. The cost is high, partly because the demand is high and the market will support high prices. But more importantly, it’s because the revenue from the fees is fed back into the system that preserves the national park and the gorillas. Those who visit them are also helping to support them.

The demand could have been expected to remain high for the foreseeable future. And then came the unforeseeable: the pandemic. “We’ve never seen this before,” Moses said to me, “to have only one group in all this time. When you compare it to before the pandemic shattered everything, it was a very big number. The local communities were benefitting.”

It’s not only Americans who have stopped coming. Rwanda has stopped receiving tourists from Europe and China as well. The economic hardship on the ground continues to grow.

Open for Business

Rwanda has opened for tourism and has been certified by the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) as having successfully adopted the global standardized health and hygiene protocols of the WTTC for dealing with COVID-19. But since the opening, tourism has been very slow to pick up again. Moses recently led his first group since March.

“At the part of our trip where we started to trek, I met one of the porters,” he said. The porters are local people who hire themselves out to accompany the visitors, carry things for them, and help them through rough patches in the mountain jungle. They are among many in the chain who are suffering from lack of work.

“It’s really sad to hear their stories,” Moses said. “They can no longer provide the essentials to their families.”

When the system breaks down on the ground level, it signals the probability of widening destruction as economic hardship grows.

The Role of Local Communities

One of the essential pillars of conservation efforts is to involve local communities. If the success of the conservation efforts also benefits the local people, they become part of the effort. If they are struggling to survive themselves, and the conservation efforts only make their lives more difficult, the efforts are not likely to succeed.

If a poor man struggling to feed his family is offered a hefty bounty to kill a gorilla and supply its head to an international black market, or to kidnap a baby gorilla to sell to a zoo abroad, it’s going to be hard for that man to turn down an offer of what would be a small fortune in that economic environment, if it means watching his family go hungry.

The villagers around Volcanoes National Park, where the gorillas are protected, receive a small percentage of the park fees and it brings them into the struggle to protect the gorillas. The tourism concessions also provide jobs.

“The villagers are shown how tourism can benefit them,” said Nice. “But since tourism stopped, they are no longer getting anything. If it stays stopped, maybe they will go back to poaching if it’s essential to get food for their families.”

Villagers honor the borders that keep them out of the park because they are part of the deal. But if they become desperate for food, they may need to go back into the park forest to cut bamboo or to hunt for bush pigs, or even elephants.

Dominoes Fall

Tourism provides the financial support to power the conservation efforts. When the flow of money cuts off, the problems mount up along the chains of cause and effect as the dominoes fall.

I’ve seen how the spreading of economic distress mounts up wherever tourism economies are shattered, such as in Egypt. For several years following the Arab Spring of 2011, tourism in Egypt almost ceased to exist; and the economic suffering of the many families who depend on tourism income was prolonged to an excruciating extent.

We’ve seen the same effect in various places and times after a terrorist attack or disease outbreak. The economic collapse spread rapidly in many places after 9/11. But we’ve never seen such widespread and sustained damage as we’re seeing with the COVID pandemic.

Even though tourism revenue has essentially stopped, Moses says, the gorillas are safe, for now. Extra precautions are being made to keep the gorillas safe from infection of COVID. The distance required has been doubled to 12 feet. People who want to go on a trek have to show a certificate that proves they were tested for COVID infection within the previous 72 hours. And the infrastructure of the park and its protective system is still in place, though everything is under economic pressure.

For those who have wished they may want to go see the endangered mountain gorillas, our biological cousins, there is now an extra motivation.

Besides your own pleasure, fascination and edification, and the broadening of your world view that the gorilla experience brings with it, you can include your role in helping to preserve the wonderful animals for our future and our descendants – which is needed now, more than ever.

David Cogswell is a freelance writer working remotely, from wherever he is at the moment. Born at the dead center of the United States during the last century, he has been incessantly moving and exploring for decades. His articles have appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, Fortune, Fox News, Luxury Travel magazine, Travel Weekly, Travel Market Report, Travel Agent Magazine, TravelPulse.com, Quirkycruise.com and other publications. He is the author of four books and a contributor to several others. He was last seen somewhere in the Northeast U.S.

David Cogswell is a freelance writer working remotely, from wherever he is at the moment. Born at the dead center of the United States during the last century, he has been incessantly moving and exploring for decades. His articles have appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, Fortune, Fox News, Luxury Travel magazine, Travel Weekly, Travel Market Report, Travel Agent Magazine, TravelPulse.com, Quirkycruise.com and other publications. He is the author of four books and a contributor to several others. He was last seen somewhere in the Northeast U.S.