In 1783, in the city of Lyon, a 32-year-old engineer and inventor did something remarkable: He unwittingly gave birth to river cruising as we know it today.

On what was presumably a warm day in mid-July, thousands of Lyonnaise gathered along the banks of the Saône to watch the Frenchman chug upstream in a boat measuring 150 feet long and 16 feet wide. They were witnessing a spectacle never before seen: the world’s first successful voyage by steamboat.

Up until this time, ships had been propelled by wind or by men rowing. The opportunity to see a boat move on its own power, without sails or oars, drew curiosity seekers, scientists, engineers, businessmen and skeptics. Spewing plumes of smoke from its chimney, the Frenchman’s boat must have appeared as a fire-breathing dragon to those onlookers.

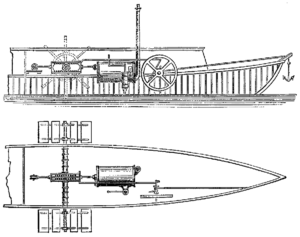

Named Pyroscaphe (“fire boat,” derived from Greek), the steamboat was powered by a two-cylinder engine that turned a pair of paddlewheels, each 15 feet in diameter and capable of pushing the boat upriver against a strong current. With a crew of only three, the boat puffed upstream for 15 minutes to cover a distance of nearly four miles, cut short when Pyroscaphe began to break apart under the constant pounding of its powerful engine. Before anyone ashore could notice, the quick-thinking Frenchman maneuvered the boat ashore and bowed to a cheering crowd.

Not the First, But the First Successful Steamboat

Propelling a boat by steam engine had been tried before, but always with the disappointment of watching one’s boat slowly break up and descend beneath the water’s surface. The weight of the engines and their constant pounding were more than the boats could bear. You’d be hard-pressed to find a more tragic story of steamboat experiments gone awry than that of French engineer and inventor Claude François Joseph d’Auxiron.

In December of 1772, a little more than 10 years before Pyroscaphe chugged upstream in Lyon, d’Auxiron began work in Paris on a boat that he would equip with a steam boiler installed on a brick foundation for fire protection. Parisians had never seen anything like his odd boat. Parisians had never seen anything like d’Auxiron’s odd boat, and many made fun of it. Some even went so far as to make threats against it; d’Auxiron responded by having the military guard his boat.

In 1774, he moved this boat from Île des Cygnes (Isle of Swans) to Meudon, in the southwest suburbs of Paris. While docked in Meudon, d’Auxiron’s boat mysteriously sank one night in September 1774. Though foul play was suspected (French inventors were not above sabotaging their peers), indubitably the culprit was the heavy steam engine and its brick foundation. The loss was devastating for d’Auxiron as the sinking of his boat also submerged an agreement he had with the French government for a 15-year license to operate commercially. It was a huge financial blow for d’Auxiron that took a toll on his well-being. After three years of lawsuits with stockholders, not yet 47 years old, he suffered a stroke and died.

Across the Atlantic, a decade before d’Auxiron’s experiments, the American gunsmith William Henry equipped his boat with a steam engine in the “first attempt that had ever been made to apply steam to the propelling of boats,” wrote Robert Henry Thurston in his biography, “Robert Fulton: His Life And Its Results.” On its maiden voyage near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, however, the sternwheeler promptly sank into the murky depths of the Conestoga River.

Still, Henry played a critical role in the development of the steamboat. His experiments on the Conestoga impressed his 12-year-old Lancaster neighbor, Robert Fulton, who is widely credited with inventing the steamboat. As we’ll see later on, Fulton gave credit to the protagonist that we introduced in Lyon.

At age 23, Fulton moved to Europe, where he lived for the next two decades. The young engineer became swept up in “Canal Mania,” a period of intense canal building in England and Wales. Of particular interest for Fulton was the canal systems’ locks. He was convinced that there must be a more efficient system to move boats up and down the canals than the locks that filled with and emptied water to raise or lower boats and send them along their onward journeys. In 1794, an idea came to fruition when Fulton obtained a patent for the inclined plane, a type of cable railway that raises or lowers boats between varying water levels.

One such example that you can see today is on France’s Marne-Rhine Canal, where the Saint-Louis-Arzviller inclined plane replaces 17 locks and eliminates 2.5 miles of travel. Guests on my hosted barge trips through Alsace get to experience the thrill of ascending or descending the inclined plane just outside the charming village of Saint-Louis. The time-lapse below shows how the incline works. It was filmed by David Weymouth, who barged Alsace with me in October of 2019.

At around the same time that Fulton obtained a patent for the inclined plane, he had began working on ideas for steamboats, recalling what he had learned as a boy from his neighbor William Henry. In 1803, the 38-year-old Fulton managed to sink an experimental steamboat operating from the same island in Paris where d’Auxiron’s boat sank a few decades earlier.

In 1806, having learned from his experiments in France, Fulton returned to the United States, confident of a successful steamboat venture. The next year, he launched the North River Steamboat, which carried passengers along the Hudson River (known then as the North River) between New York City and Albany, a journey of 150 miles that spanned 32 hours. The 1940 film Little Old New York is based on Fulton’s ambitions to build the North River Steamboat.

The North River Steamboat began regular passenger service in September of 1807. The steamboat, which known as Clermont, left New York on Saturdays at 6 p.m. and returned from Albany on Wednesdays at 8 a.m. In its first year of operation, the North River Steamboat was profitable, encouraging Fulton and his business partner, Robert Livingston, to commission two additional steamboats. Livingston died in 1813 and Fulton, two years later.

After the deaths of Livingston and Fulton, their company, which had enjoyed a monopoly in New York waters, opened to competition. Livingston’s heirs had granted an exclusive license to Aaron Ogden to operate a ferry service between New York and New Jersey, but Thomas Gibbons and Cornelius Vanderbilt established a competing service. A legal battle ensued, and the courts dissolved Ogden’s monopoly in 1824. By 1840, there were more than 100 steamboats in operation in New York waters. The Steamboat Era was, well, in full steam.

While Fulton is credited with inventing the first steamboat, the American engineer and inventor graciously acknowledged our Frenchman, proclaiming, “If the glory … belongs to any one man, it belongs to the author of the experiments made on the River Saône at Lyon in 1783”.

That takes us full circle back to Lyon. How Pyroscaphe’s inventor ended up in Lyon is an interesting story in itself, with sufficient drama for a PBS Masterpiece production: love, jealousy, imprisonment and the life of a celebrated nobleman ending in bitterness and poverty. For that story, we’ll need to wind back the clock 32 years to visit the Doubs river in eastern France. There, in a commune known as Abbans-la-Ville (now known as Abbans-Dessus), a castle stands with the inscription, “Claude Dorothée Marquis de Jouffroy d’Abbans, 1751-1832, Inventa Ici Le Bateau A Vapeur (invented the steamboat here).”

A Tinkerer in Good Company

In 1751, de Jouffroy was born to a noble family in Roche-sur-Rognon (now Roches-Bettaincourt) in France’s Champagne region. He spent his childhood years more than 100 miles south in the family castle near Besançon.

Besançon serves as the seat of the regional council of the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region, and for someone with an inventive mind, there was no better place to grow up. Our ill-fated d’Auxiron was born in Besançon as was the poet and novelist Victor Hugo. The region brims with tinkerers, skilled tradesman and inventors.

Besançon has been France’s watch-making capital since shortly before the French Revolution, and it is perhaps not entirely without coincidence that the working mechanisms of timepieces were what lured de Jouffroy into the world of invention. As a boy, he disassembled the castle clocks to solve the mystery of how they worked. Fortunately, he managed to reassemble them in working order.

The young de Jouffroy demonstrated an aptitude for engineering, wrote Alfred Prost in the biography, “Le Marquis de Jouffroy d’Abbans: Inventeur de l’Application de la Vapeur À La Navigation,” published in 1889. He might have pursued an early career in engineering, but his parents had other plans for him: a career solider, a profession that they felt was worthy of the family’s aristocratic heritage.

At the age of 13, de Jouffroy began military instruction in the court of Versailles where he served as a page. While at Versailles, he became intrigued with the lessons from a master mathematician, Louis Charles Victoire Trincano, who had penned the ambitiously titled, “Complete Treatise on Arithmetic for the use of the Military School of the Company of the Light Horses of the Ordinary Guard of the King.” Slowly but surely, de Jouffroy was acquiring the necessary knowledge and skills that would be required to build his steamboat.

When de Jouffroy returned home to the castle near Besançon, his father found him an assignment in an infantry regiment, a fashionable assignment at the time for nobility. While serving in the regiment as a second lieutenant, de Jouffroy and his commanding officer, Comte d’Artois, described as an elegant tall blond with black eyes, had affections for the same lady. Their rivalry escalated to the point of an altercation – one not without consequence for de Jouffroy. After multiple infractions (some say alleged) and on what may have been questionable charges, de Jouffroy was sent to prison in the Lérins Islands. The islands, offshore from the city of Cannes, were home to Fort Ste-Marguerite, the same prison that had held the so-called Man in the Iron Mask during in 17th century.

From his cell overlooking the harbor, de Jouffroy observed the large ships of France’s Royal Navy, propelled by sails and galley convicts chained to their benches to row the vessels. An idea hatched in de Jouffroy’s head: Could there be another means to propel the ships? His steamboat was beginning to take shape.

While in prison for two years, de Jouffroy consumed books about navigation and ruminated on ideas that might result in a successful steamboat. Upon his release in 1773, he returned to the castle near Besançon, but left for Paris soon afterward to study steam engines to see if they might have applications for steamboats.

He Went to Paris Looking for Answers

Paris was the epicenter of French intellect and ingenuity. In 1753, the French Academy of Science had launched a competition aimed at finding ways to supplement sail power. The winner, a Swiss mathematician and physicist named Daniel Bernoulli, recognized that steam could be used to supplement sail power but he deemed steam as being an inefficient method.

In fact, steam was inefficient. In 1712, the English inventor Thomas Newcomen unveiled his “atmospheric engine,” the world’s first practical device to harness steam to produce mechanical work. The engine was used to pump water out of tin and coal mines that were prone to flooding. “The problem was that Newcomen’s engine required the cylinder itself be alternately heated and cooled to generate work, which because of thermal inertia of the cylinder walls (usually copper) was a slow process that wasted a lot of heat,” wrote naval architect and historian Larrie D. Ferreiro in his book “Bridging the Seas: The Rise of Naval Architecture in the Industrial Age, 1800-2000”

Enter the Scottish inventor James Watt, who significantly improved the performance of the Newcomen engine with his Watt steam engine. And that brings us back to Paris.

In the French capital city, de Jouffroy found his way into scientific and engineering circles in which there was buzz about a new hydraulic achievement on Chaillot Hill, which faces the Eiffel Tower across the Seine. The Chaillot machine, powered by Watt’s new improved steam engine, was designed to pump water from the Seine to Château de la Muette along Rue de la Pompe, a street named for the “fire pump.”

The project was spearheaded by Auguste Charles and Jacques-Constantin Périer, who were great builders at the time. The two brothers had plans to supply the city of Paris with water through their new pumps powered by steam.

While in Paris, de Jouffroy met with the Périer brothers, discussing the possibility to use steam engines to propel boats. However, he and the brothers disagreed on aspects of how much propulsion would be needed. The disagreement escalated into a dispute, and their relationship would remain contentious until the end.

Undeterred, de Jouffroy returned home to build an experimental boat using a steam engine. While his father showed little interest, his sister was confident that her brother would succeed. On a visit to his sister in Baume-les-Dames, de Jouffroy spotted a beautiful lake and decided to conduct his experiments there, building a steam engine with the help of a local coppersmith.

The engine was installed on a boat, 40 feet long, with an engine that moved oars equipped with hinged flaps modeled on the form of the webbed feet of waterfowl. In June and July of 1776, de Jouffroy experimented with his boat on the Gondé basin, where the Cusancin flows into the Doubs, at Baume-les-Dames. He briefly navigated the boat, but the oars on each side prevented passage through the locks. He considered his first boat a relative failure, but had a better idea: to replace the oars with paddle wheels, adapting James Watt’s designs to build a parallel-motion, double-acting steam engine driving two large paddle wheels, one on each side of the hull.

Success in Lyon, Sabotage in Paris

That brings us back to Lyon, with de Jouffroy bowing to the crowds on his nearly broken steamboat. The imaginative Frenchman made quick repairs and adjustments to Pyroscaphe, and in August of 1983, his steamboat carried freight and passengers on the Saône.

The marquis continued experimenting on the river for 16 months. He applied for a license to launch a steamboat company in the hopes of recovering his investments. The license would have given him a 15-year monopoly more or less. But France’s Minister of Finance, who consulted the Academy of Science, replied, “It appeared that the test made in Lyon did not meet the required conditions.” The minister would grant a license only if the steamboat could be demonstrated on the Seine, a difficult, if not impossible, proposition that would require a new steamboat.

De Jouffroy had spent a fortune already and was unable to muster the financial resources to continue his fight for a license. Why would the minister demand that the steamboat be demonstrated on the Seine? What dare not be said was that the Academy of Science could not allow Lyon to succeed where Paris had not. But the more sinister motive was that the influential Périer brothers made the demand, from which they would profit handsomely. The brothers offered to build a boat for de Jouffroy for 100,000 livres, an exorbitant amount of money at the time. He could not afford it. The Périer brothers later entered a relationship with the young American Robert Fulton, whose steamboat was launched on the Seine in 1803.

With his spirit broken and now impoverished, de Jouffroy retired in 1831 to the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris, where he died a year later of cholera. His body is buried in a mass grave.

A century later, in 1884, France recognized the the inventor by erecting a statue of Jouffroy in Besançon.

Next week, we’ll look at how steamboats led to the expansion of the river cruise industry.

If You’re in Lyon

Today, river cruisers retrace part of the route where de Jouffroy’s steamboat chugged upriver as they make their way along the Saône on voyages between Chalon-sur-Saône and Lyon. I wonder how many of those who have stood on the decks admiring the Lyonnaise landscape know it was here that river cruising was born. If you’re in Lyon you can walk, or cycle, the route, from quai de l’Archevêché (today quai Romain Rolland) to l’île Barbe. I’ve cycled along this route several times while visiting Lyon without knowing the story of the “fire boat” on the Saône. Often, Rhône and Saône river cruises will touch on both rivers.

Barge on the Doubs

In October of 2021 and again in April 2022, I’ll be barging on the Doubs river, and visiting Besançon. Join me for a beautiful voyage through one of the most intriguing parts of France. Learn more at this link.

This article was originally published at River Cruise Advisor.

An avid traveler and an award-winning journalist, Ralph Grizzle produces articles, video and photos that are inspiring and informative, personal and passionate. A journalism graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ralph has specialized in travel writing for more than two decades. To read more cruise and port reviews by Ralph Grizzle, visit his website at www.avidcruiser.com.

An avid traveler and an award-winning journalist, Ralph Grizzle produces articles, video and photos that are inspiring and informative, personal and passionate. A journalism graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ralph has specialized in travel writing for more than two decades. To read more cruise and port reviews by Ralph Grizzle, visit his website at www.avidcruiser.com.